Ceintuurbaan 254

1072GH Amsterdam

24 – 28 March 2012

2pm till 8pm

OPENING RECEPTION: 23 March, 8pm

Press releaseYou killed the Underground Film or The Real Meaning of Kunst bleibt ... bleibt ...

Malcolm Le Grice

When I started to make film in the 1960’s I knew of very few points of reference for work like mine. I had heard a little about the American ‘Underground’ before seeing any of the films, then through the London Filmmakers Co-operative, I started to see experimental film and discuss this with fellow film-makers, particularly Peter Gidal. At the beginning I knew nothing of any European ‘Underground’ films but then learned of Kurt Kren in Vienna and Birgit and Wilhelm Hein in Köln. When I saw their ‘Roh Film’ and related this to my ‘Castle One’ and ‘Little Dog for Roger’, I at once recognised a real similarity in instinct and attitude that had translated itself into exploring similar areas of cinema – or perhaps more correctly – anti-cinema. ‘Roh Film’ like my own work of the time was a kind of pre-punk cinema – wild, extreme and aggressive. It applied concepts of montage, like the ‘Merzbild’ of Kurt Schwitters, to film. Actually these were concepts of collage – a physical ‘attachment’ – gluing together of film material - not the same as ideas of film montage from Eisenstein or Pudovkin. And for ‘Roh Film’ even the term concept is misleading. The assemblage of the film was improvised, intuitive, often random – a “zak-zak” (W. Hein) forcing together of images and sounds – dynamite to explode conventional cinema into fragments – perhaps, but only perhaps, for re-building in a different way.

Seeing the early films of B&W Hein told me that my own crazy experiments were maybe not so crazy after-all. They organized a tour for me in Germany and Austria in 1968 which began a dialogue – often endless hours and gallons of beer, talking together well into the night in their Lupusstrasse, Köln apartment. This began a friendship and sense of a basically shared ‘philosophy’ that lasts to the present – fortunately for me it remains a friendship with both Birgit and Wilhelm following their separation, each exploring their own artistic direction.

‘You killed the Underground Film ...”. So what was the Underground Film and who killed it? In the 1960’s I think we ‘radical’ film-makers all talked of ourselves as ‘Underground’. That was the word then – not so much, Avant-garde or Experimental. ‘Underground’ variously linked with: student protest against the Vietnam war; was part of a mainly ‘youth’ revolt against capitalism, consumerism, class based dress codes and life-style; and often ran parallel to rock music. The classic Underground cinema was transgressive. Jack Smith’s ‘Flaming Creatures’, for example, by confronting the representation of un-repressed sexuality, was subject to censorship and police raids. Underground film attacked the explicit censorship imposed by law but also the implicit self-censorship of the film-maker.

Underground film originally lacked any context in ‘official’ culture. With extreme ideas about society and individual freedom beyond the scope of existing artistic and cultural institutions, it went underground, often establishing its own special screening arrangements outside the established cinema circuit. But not all radical or counter cultural film fitted the mould of ‘psycho-social’ transgression. Works that explored new cinematic forms, poetic content and the medium itself, were equally outside mainstream cinema and other artistic institutions. Engagement with mainstream commercial cinema was almost impossible. The whole social function, expectation of audiences and production and exhibition systems were un-penetrable - it was and still is ‘the enemy’. In seeking a new context two major alternatives gradually emerged. One was incorporation into art galleries the other into art education. But each of these also involved suspicion and uncertainty on the part of radical film-makers. While the ‘Underground’ opposed commercial cinema, it also opposed the idea of art as a commodity and with it the linked system of dealerships, museums and galleries. It was also strongly anti-academic. But even film-makers who wanted to work with the art world and academic institutions still found experimental film marginalised.

So who killed the Underground Film? Well to some extent probably artists like me who stressed the Avant-garde, Experimental concept of film and now of video and digital cinema stepping away from the Underground’s transgressive roots. But also the transgression changed. In contemporary western culture, many of the life-style conflicts have disappeared even if the underlying political inequalities and repressions remain. Outside the political arena it is increasingly difficult to find content that shocks. Mainstream cinema and television exploit all forms of sexuality and violence on a daily basis. The media and news corporations have made us immune spectators. But even within our own experimental film history, as well as more aesthetic, abstract or poetic directions, the underground film’s broad counter-cultural trajectory has itself sub-divided into specific territories: feminism; gay identity; issues of race and ethnicity; or socio-political documentary.

So what of ‘You killed the Underground Film or Kunst bleibt ... bleibt ...’ and Wilhelm Hein’s continuing work as a film-maker, artist? This long, and still growing, work has no stylistic constraints – it can go in any direction it likes or Wilhelm Hein likes. Or maybe even where Wilhelm does not like. It is still an underground film where anything – any thought, any idea, any image – can and must be accepted. This includes the unthinkable, the unsavoury, the taste-less or the trivial. As with earlier works like ‘Manson, Biggs, and Hein’, (made with Birgit) Wilhelm continues to find his subjects – resolutely points his camera outside the conventional and acceptable. His attitude is not didactic – he is not dealing with ‘issues’ – he has a real engagement with the people he films. His films remain raw, his nerves and sinews remain exposed and the works expose us beyond our expectations and desire. And they are good and engaging works of cinema. He has resisted academic engagement and remains abrasive in his relationship with the institutional world of art. He has never split the elements or themes of his work into their sub-categories and continues to explore politics, sexuality, psychology, image, aesthetics, movement and temporality as integrated and inseparable elements of his life and art. He reminds us, we other film-makers, that our job as artists is to explore any conceivable subject without compromise.

Malcolm Le Grice

2 March 2012

Material:

Interview You killed the Underground Film or The Real Meaning of Kunst ... bleibt ... bleibt, Passenger Books, Berlin, 2009

You killed the Underground Film or The Real Meaning of Kunst bleibt ... bleibt ... website

W+B Hein Kunstforum, Bd. 106, p. 169, 1990

W+B Hein; Dokumente 1967 – 1985. Fotos, Briefe, Texte Kinematograph nr. 3/1985, Deutsches Filmmuseum Frankfurt am Main, 1985

Superman and Superwoman Substance 37/38, University of Wisconsin Press, 1983

On Structural Studies (Birgit Hein) Structural Film Anthology, ed. Peter Gidal, British Film Institute, 1976

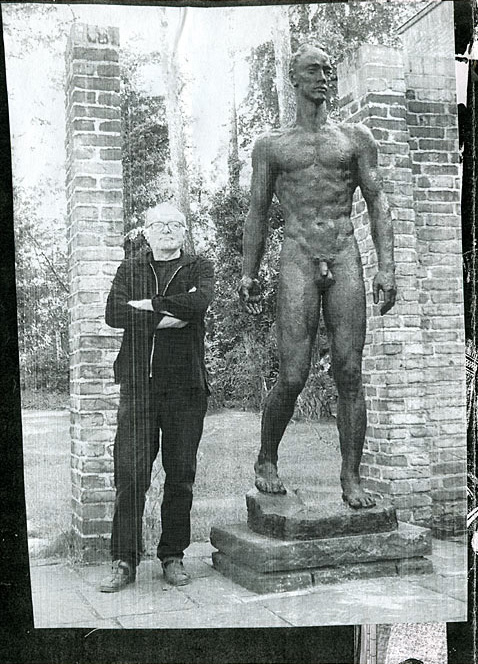

Photo: Annette Frick

To stay informed please sign up for the mailing list:

LOST PROPERTY